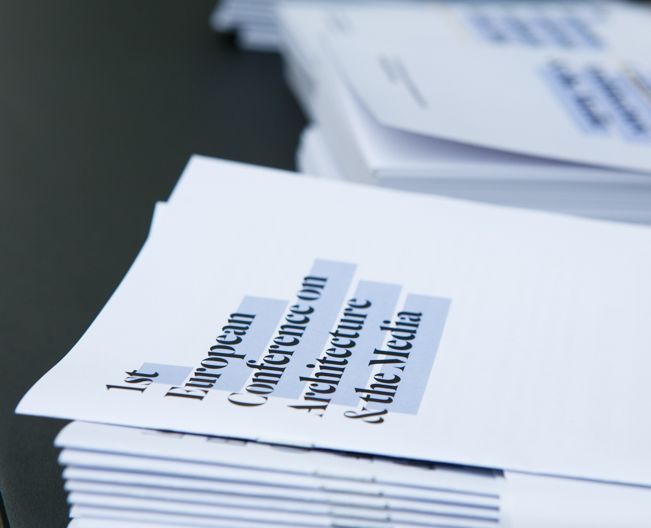

Architecture & the Media: a Recap

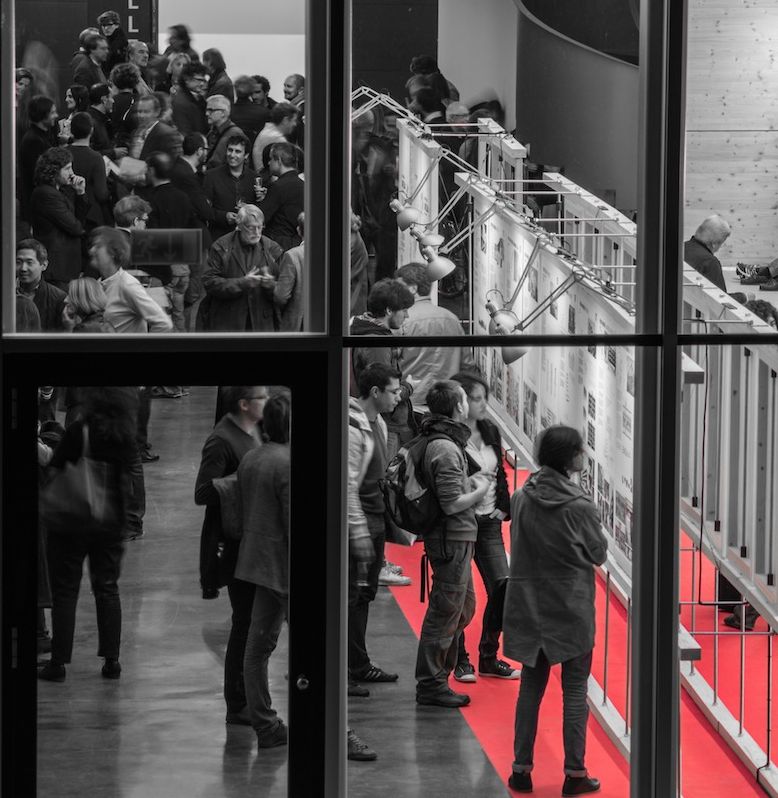

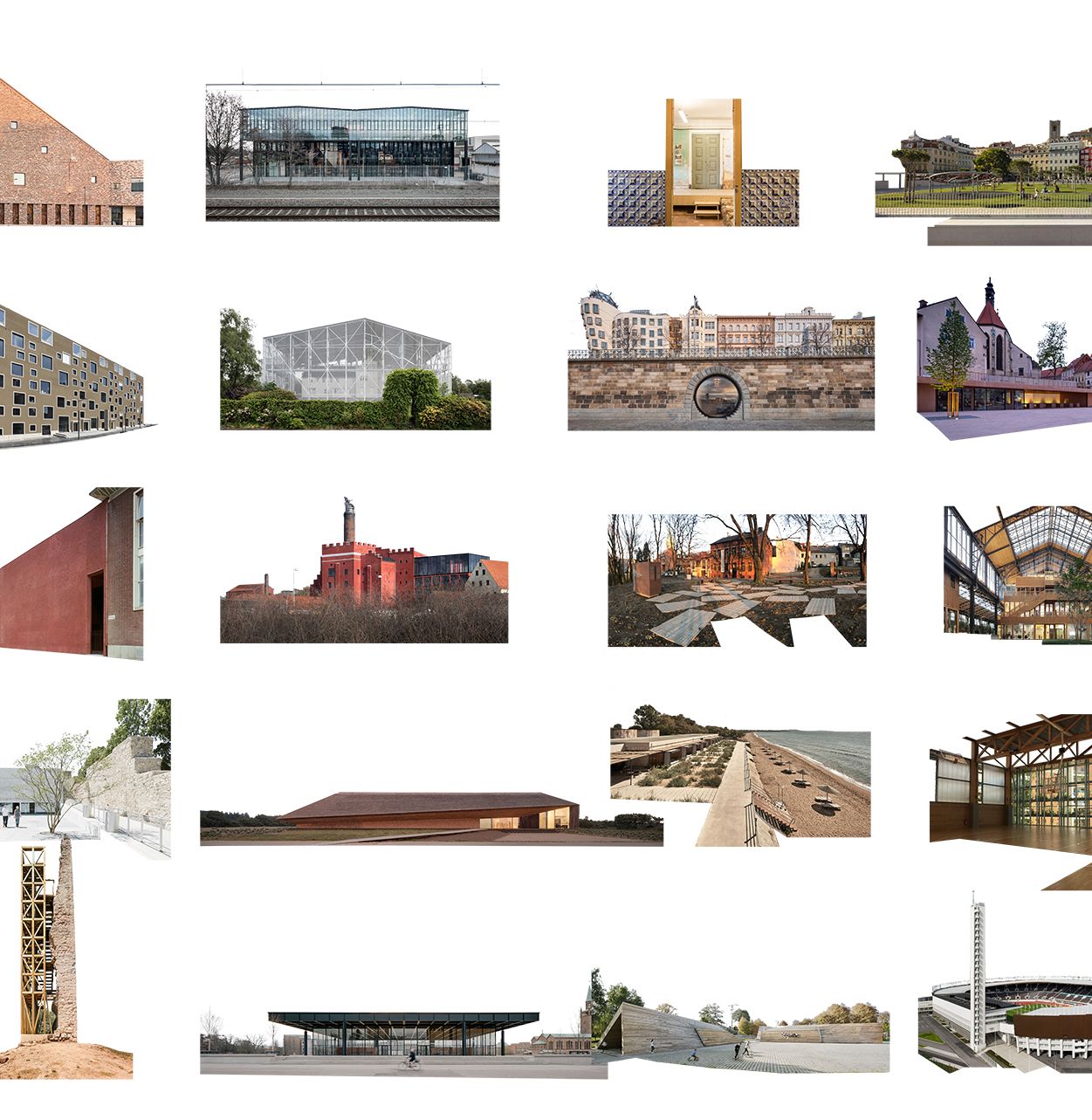

The proposal of the 1st European Conference on Architecture & the Media was for twenty of the most influential communicators on the continent to come out of their editorial offices and join forces to share experiences about how to disseminate architecture. The idea was especially to see how high-quality projects, both for buildings and for public space, can gain visibility in the media. They were confronted with a very demanding audience: other journalists, cultural institutions and organizations, communication professionals, architects, and lovers of architecture in general.

The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has said: "Architecture has a serious problem with communication." The interest aroused by the conference confirmed this. Despite the fact that the provocations of Koolhaas do not tend to leave anyone indifferent, his past as a journalist entitles him to discuss this issue.

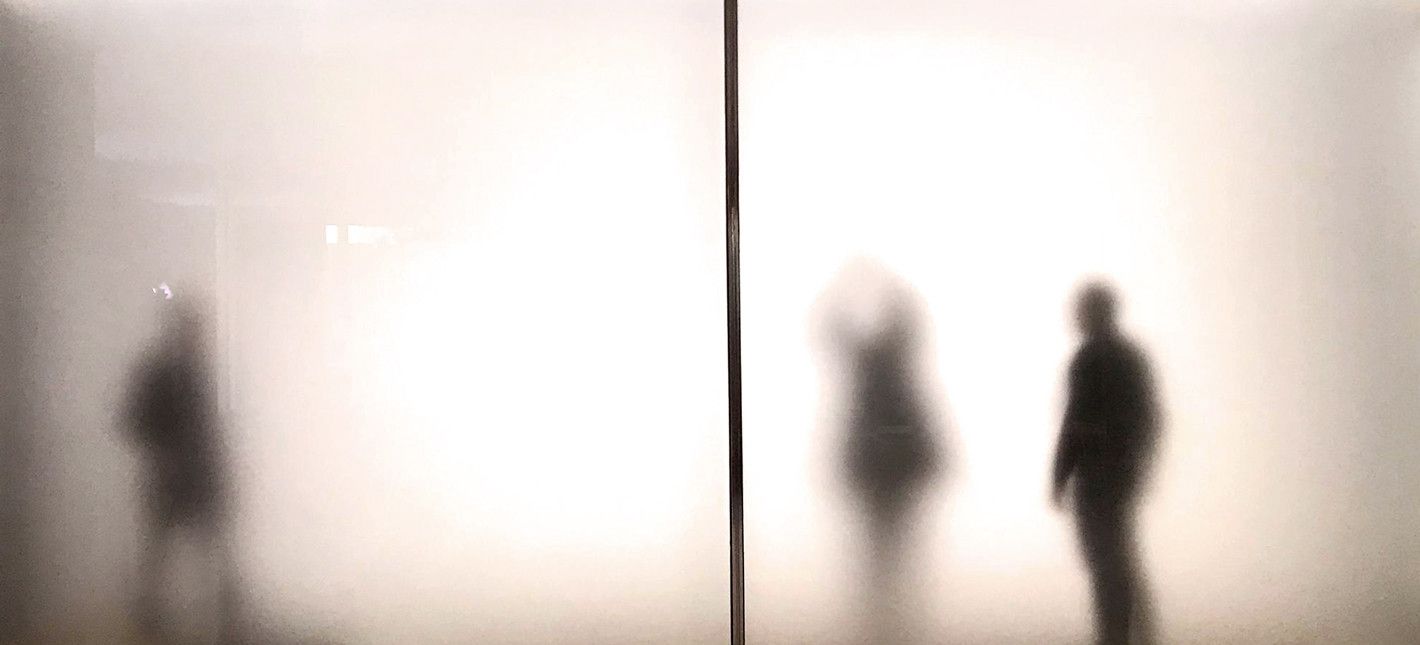

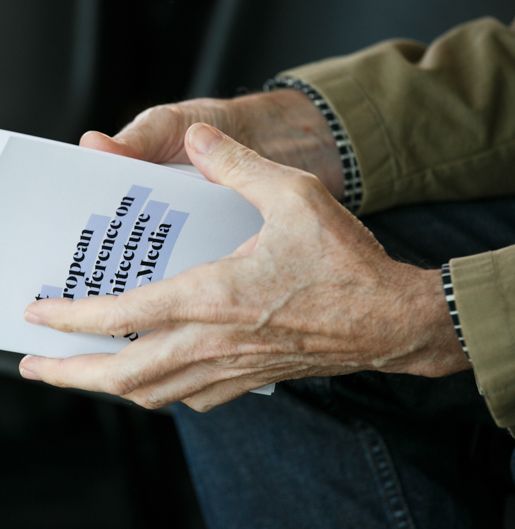

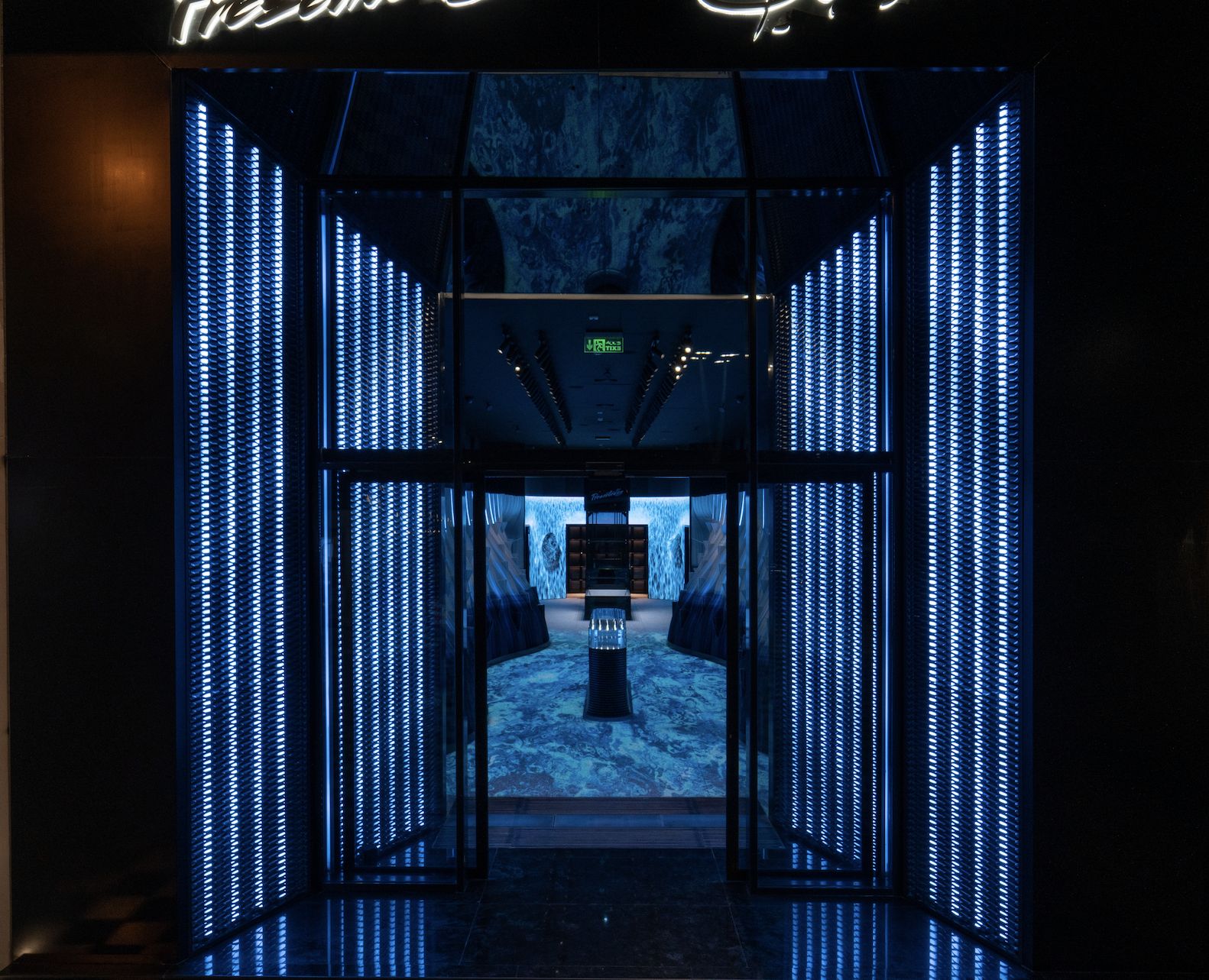

The 1st European Conference on Architecture & the Media was organized by the Fundació Mies Van der Rohe as part of Barcelona Architecture Week and the program to publicize the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe Award. The conference was curated by two women: Miriam Giordano, a communication consultant, Director of Labóh and of Spanish-Architects and Italian-Architects; and Ewa P. Porębska, an architect and Editor in Chief of the Polish magazine Architektura-Murator. The venue chosen was the Barcelona Pavilion, the icon of modern architecture that Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe and Lilly Reich – often forgotten – designed for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. This was undoubtedly a good place to reconsider how we communicate architecture.

© Anna Mas

Anna Ramos, Director of the Fundació Mies van der Rohe, had maintained on numerous previous occasions that the intention of the encounter was to "analyze in depth the role of high-quality journalism in the dissemination of architectural culture, how it is understood by different audiences, and to construct a social debate on important issues for architecture."

However, one clear question hovered over the event right from the beginning and applied to everyone in attendance: What can the agents involved in the dissemination of architecture do to ensure that architecture is better understood and appreciated by a broader audience? This was the central question of the event, which brought together representatives from the most significant publications on the European scene. They came from Italy, England, even Croatia and Poland. With scarce exceptions, the cream of communication and architecture of the old continent was there.

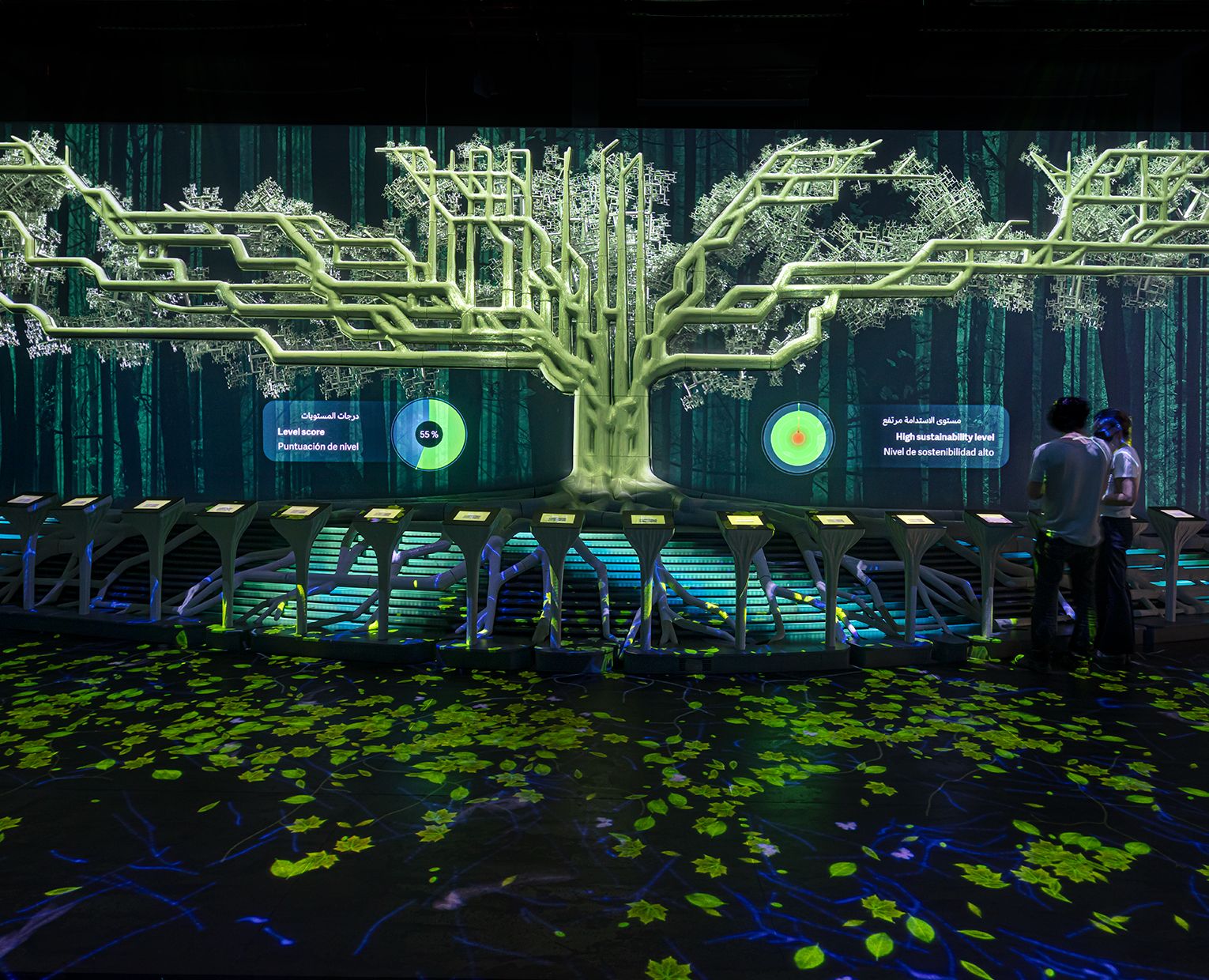

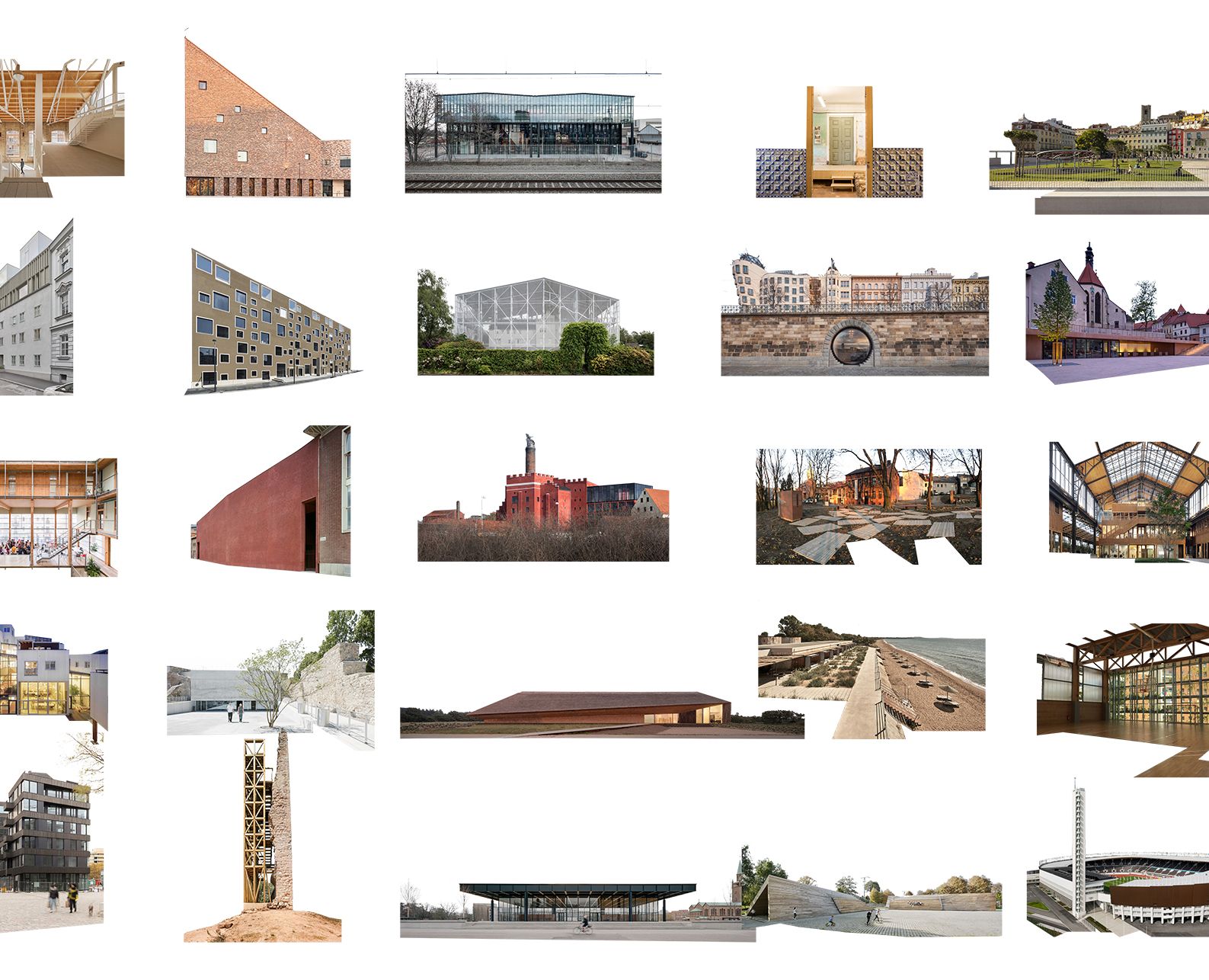

On the first day, to break the ice, the organization invited the creators of what we could call two opposing examples of architecture: Xander Vermeulen from the XVW architectuur studio, the author of the refurbishment of De Flat Kleiburg, a building with 500 apartments in Amsterdam which was condemned to be demolished; and Fabrizio Barozzi and Alberto Veiga from Barozzi Veiga, the authors of Szczecin Philharmonic, a large concert hall and auditorium that stands out in the historic center of Szczecin, Poland, thanks to its translucent whiteness. Both projects won the EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe Award, in 2017 and 2015 respectively, which helped them to appear in the pages of newspapers.

© Anna Mas

"We chose them because they seem to be an interesting starting point for the debate, since the attention they received from the press was very different. Szcecin, a public and very 'photogenic' work, received an almost viral dissemination, and the Dutch refurbishment, undertaken by a private consortium, received attention characterized by both positive and negative reviews," explained Miriam Giordano, the joint curator and moderator of the opening debate.

© Anna Mas

But, how does the press treat good buildings that do not obtain awards? One of the first journalists to talk about this was Anatxu Zabalbeascoa from El País. She did so during the opening session and under the watchful eye of numerous architects, who grimaced when they heard her say: "When you have the opportunity to visit a building … you may even think, perhaps, from the point of view of the user. But when you put this in writing, you normally run into problems. Basically with the architects. When they ask for more criticism, what they want is visibility."

Llàtzer Moix from La Vanguardia offered a tip for architects when it comes to explaining their project to the press: "Be clear about the two or three crucial decisions which make the project more understandable, which marked the project right to the end and which made it what it is, and not something else." Many architects and communication managers took note of this.

© Anna Mas

Meanwhile, the Barcelona skyline was displaying cranes again. Even without having emerged from the crisis, the capital is again showing signs of being the cradle of construction. The tourists taking selfies outside the Pavilion also transmit this sensation of normality. But something has changed since 2007: If before architecture was talked about a great deal in the Culture section, now the buildings have become familiar in the Politics section due to corruption, and in the Economics section thanks to the crisis.

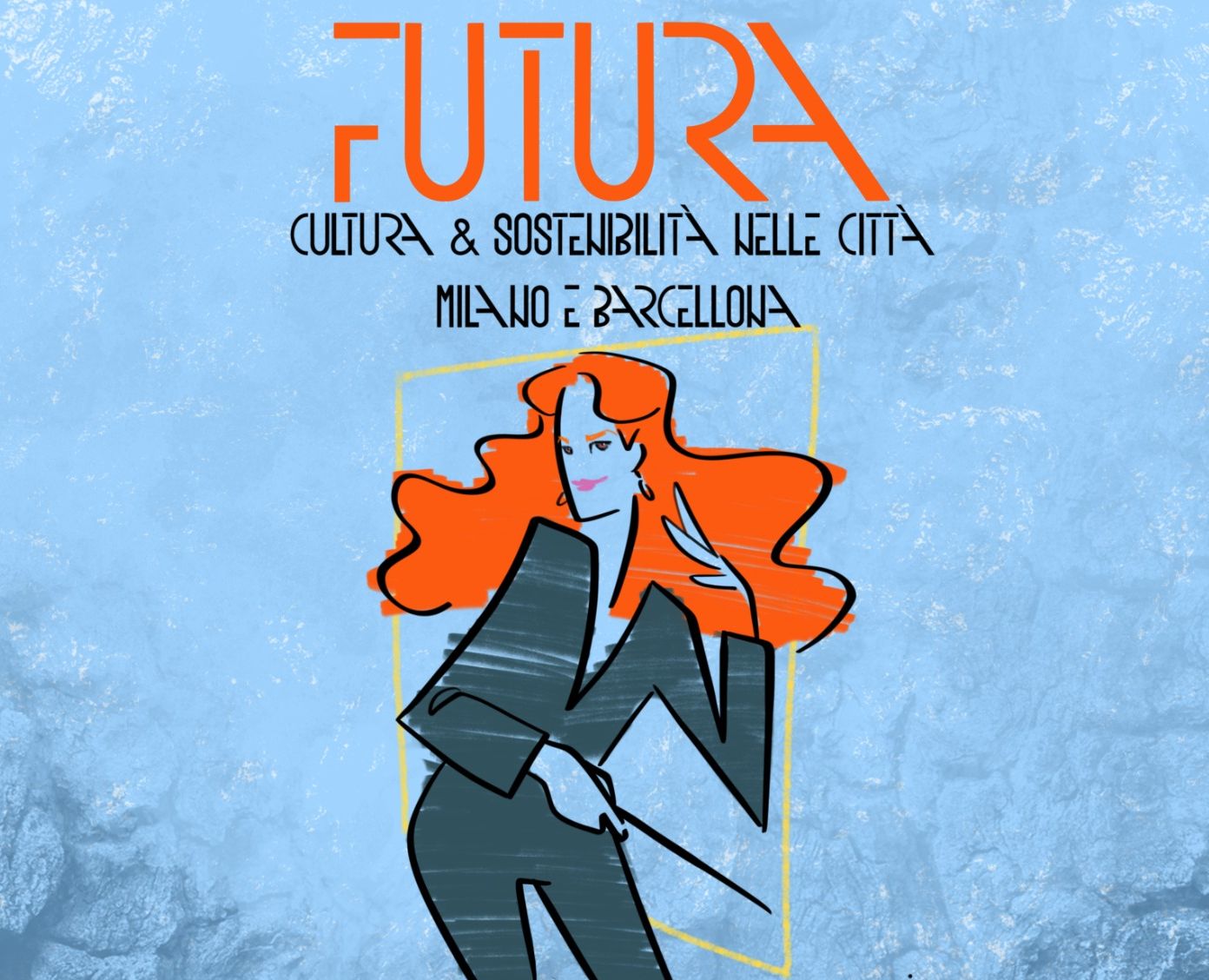

In this respect, the journalist Paola Pierotti, from Il Sole 24 Ore, outlined the direction taken by the narrative of the sector in recent years. She did so right at the beginning of the second day, while sharing a talk with Edwin Heathcote from the Financial Times, Fredy Massad from ABC, and Catalina Serra from the newspaper Ara. The Italian journalist said that the concepts dealt with by the sector have changed: We have gone from talking about "starchitects, big names, icons and marketing" to doing so about "urban regeneration and sustainability."

In any case, let us suppose that, in this new context, our project wins an award. What happens after winning the award? Journalist Catalina Serra condemned precisely this: "Recognition is often just an interesting news item, and then there is no follow-up," she complained as a representative of the written press round table. Paper is moreover limited and, in a media outlet, "there is a lot of competition for subjects," she explained.

© Anna Mas

First conclusion: Openings are popular, but there is little (or no) talk about the passing of time in architecture.

Despite the mea culpa by the press, Edwin Heathcote argued in favor of communicators: "Journalists do not have a budget. I would love to go to Caracas or to Fukushima, to talk about the architecture from there, but the first thing that they say to me is: how much is that going to cost?"

Second conclusion: paper is in crisis and this directly affects the dissemination of architecture.

The debate went even further. One of the most scathing speakers was Fredy Massad, who maintained that architecture is of "very little" interest in the pages of the big media outlets. "It is only important as a news item, not as reflection or thought," he said to an audience that totaled 250 attendees among the conference's different sessions. He added something painful to hear: "When there is a gap, then we write about architecture."

© Anna Mas

The editors of specialized magazines, who were the main actors on the second round table, are also reconsidering how to bring architecture to a wider audience. They do not have to fight as much with current affairs, but many of them are also losing analogue readers.

During her intervention, Sandra Hofmeister announced that the paper version of Detail lost 1,000 subscribers over the last year but that, however, the company gained 1,000 subscribers to its online archive. "We consider that we are not just a magazine, but also a platform with several objectives: the magazine, the archive, an award," she explained. For her part, Manon Mollard, from Architectural Review, also recognized that the sector is going through hard times, because "we only exist thanks to our subscribers." Ethel Baraona Pohl, from dpr-Barcelona, added to this: "Why don’t we begin a dialogue with our readers?" Baraona was right on the mark.

© Anna Mas

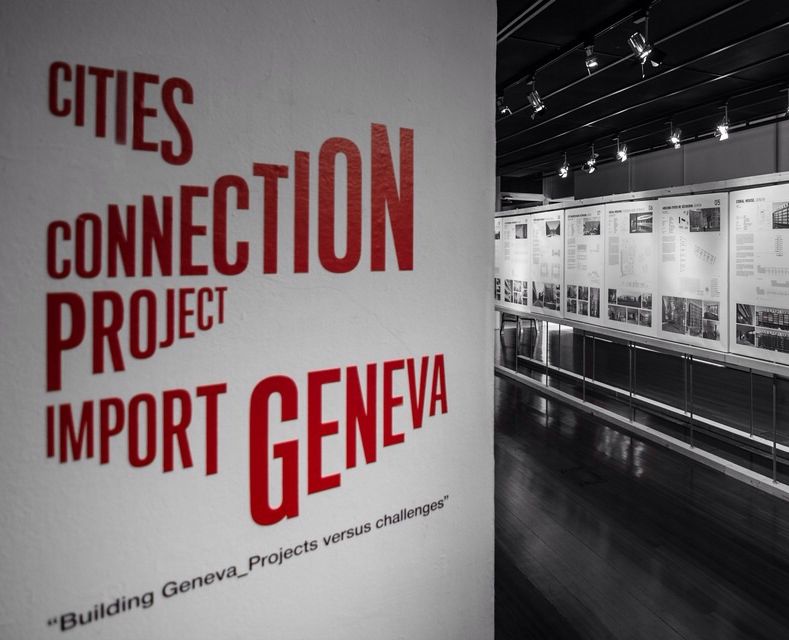

The team of Oris, the topical Croatian architecture magazine, also backed this dialogue. Frano Petar Zovko spoke in representation of the magazine: "We have diversified our activity: we hold an annual symposium in Zagreb, we organize exhibitions and training sessions, we have opened a new headquarters which includes a gallery, library, and our offices."

Third conclusion: specialized magazines are committed to diversification in order to survive.

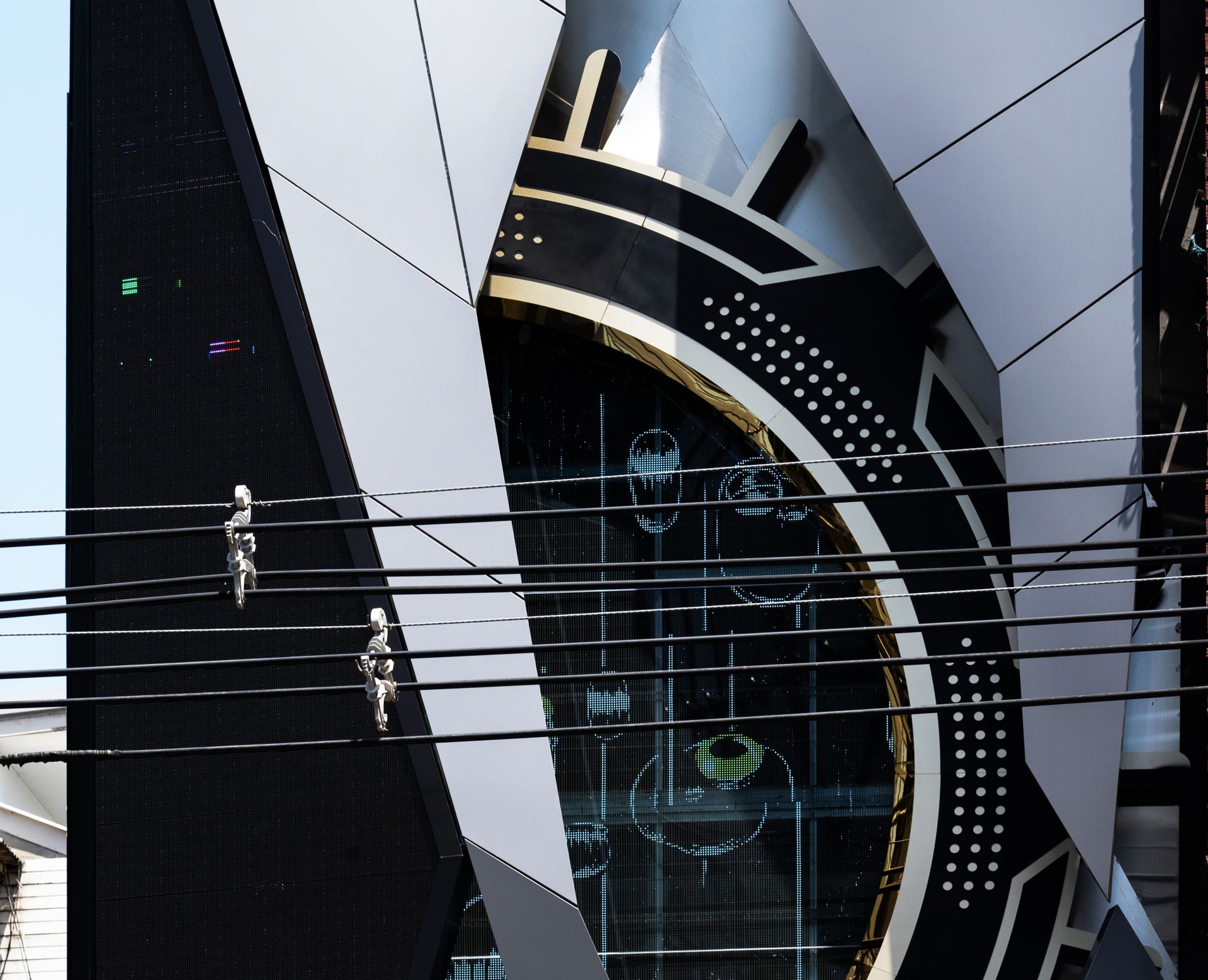

During the 1st European Conference on Architecture & the Media, the Mies – and Reich – Pavilion was also visited by students from both disciplines, representatives of cultural institutions, journalists and readers of specialized magazines, and communication professionals. This is because – and this is the fourth conclusion – architecture is increasingly read on the mobile, tablet or computer.

© Anna Mas

Someone who knows this fourth conclusion very well is Marcus Fairs who, in 2006, lost his job and decided to create his own website: a design platform that he called Dezeen. "I loved print magazines, but they were all very closed and the Internet allowed me [to address] that global culture," he said during the third and last panel. Time showed him to be right. Ten years later, Fairs became the first online journalist to receive a RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) award. This recognition was for his personal career but, at the same time, for the whole digital communications sector in architecture.

However, what normally occurs in these spaces is that the reader is very specialized. This was confirmed by Jenny Keller, from the World-Architects platform, who described the experience that she had with the obituary she wrote on David Bowie: "My main audience is architects, but this text was one of those which was read the most, although it has nothing to do with architecture. We should ask ourselves why."

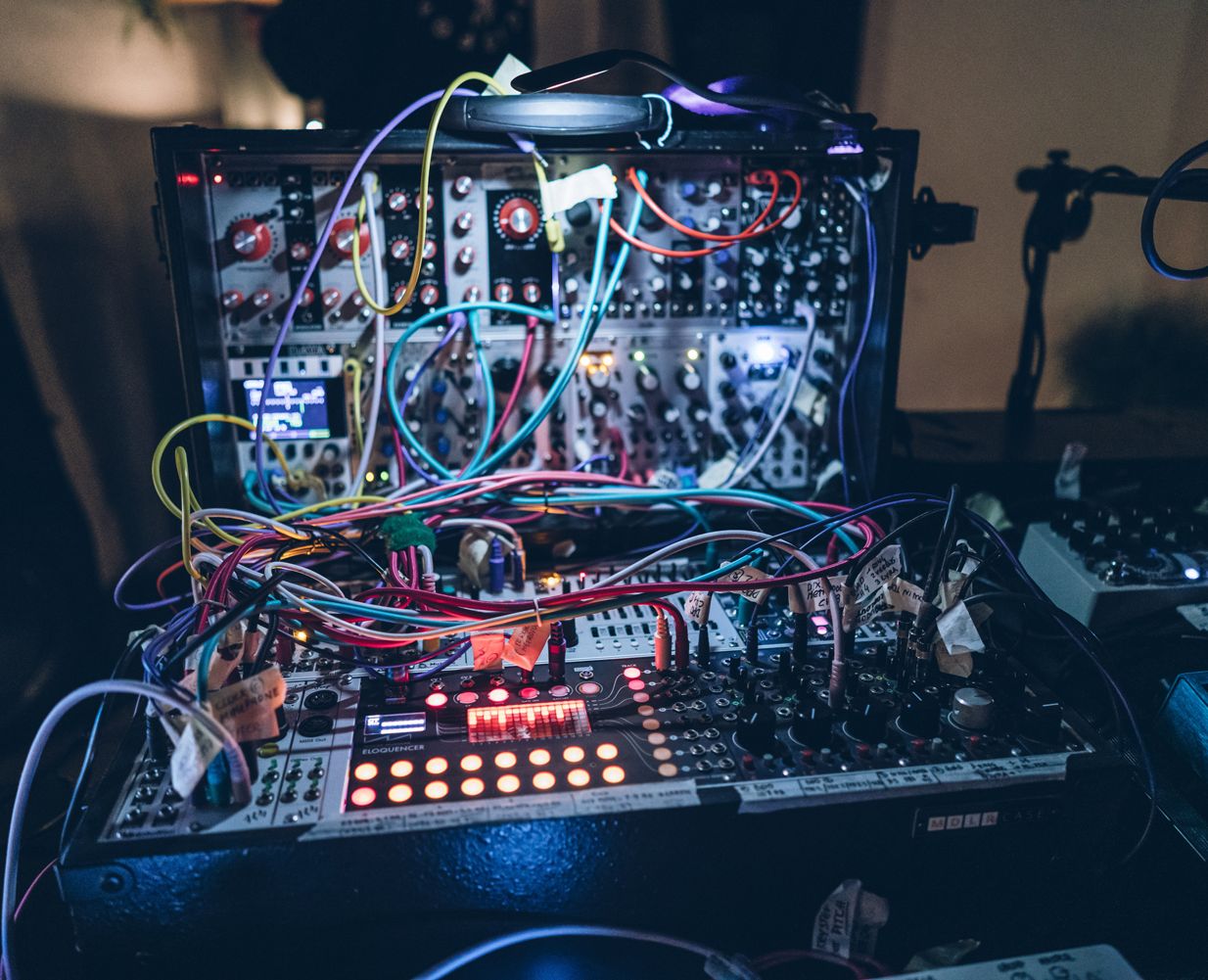

José Juan Barba of Metalocus took the first step:

The photos should be selected!

Why? We put a lot...

A large number does not help the reader to see the right image...

We put them at the bottom; in a gallery...

It’s important to include a lot of images on the mobile.

It depends on the device…

Yes, the internet is different on each medium.

It also depends on the narration that you want to promote.

© Anna Mas

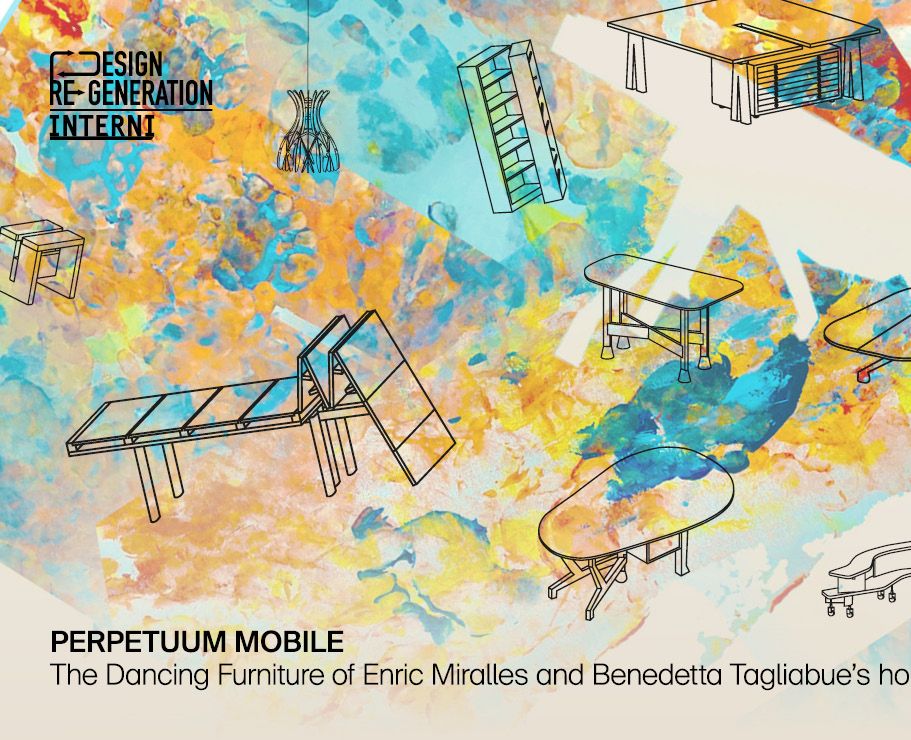

The debate on the use of photography in the digital media was opened by Barba. "I don’t understand when someone talks about photography as pornography. It’s our language! Texts are important – they help – but images are one of our main tools," he maintained, referring directly to the words pronounced by the critic Rafael Gómez-Moriana on the previous day, quoting Tom Dyckhoff. Massimiliano Tonelli, Director of Artribune also stressed the importance of videos and infographics with data as very valuable tools for online media.

Fifth conclusion: specialized readers sustain the online media, but digital tools still need to develop their full potential.

This brief exchange of views demonstrated that meeting the other – in this case, journalists, cultural institutions and organizations, communication professionals, architects, and lovers of architecture – is complementary. "Almost twenty years ago I participated in the first international meeting of architecture magazines," remarked event co-curator, Ewa P. Porębska. "It was only held once, in Montpellier in France, but it was my inspiration for many years and it made me stronger. ... This year’s Architecture & the Media conference allowed us to share experiences, analyze our successes and failures. We learnt a great deal from each other. I’m sure that it will produce results."

© Anna Mas

However, on that day our thoughts were far from Europe. We had awakened to the news of the terrible massacre carried out by Israel in Gaza: 59 Palestinians killed and more than 2,700 injured.

The dpr-Barcelona tandem made the right decision on projecting a slide about this. One of those which sustain a few seconds of silence: "Books are louder than bombs." It was impossible not to think, in the Barcelona Pavilion, about the transforming role of Architecture and also about that of Communication. Like that, in capitals. Because we all inhabit the same planet. And the story needs to be told – and told well.

This article originally appeared in World-Architects.

© Anna Mas

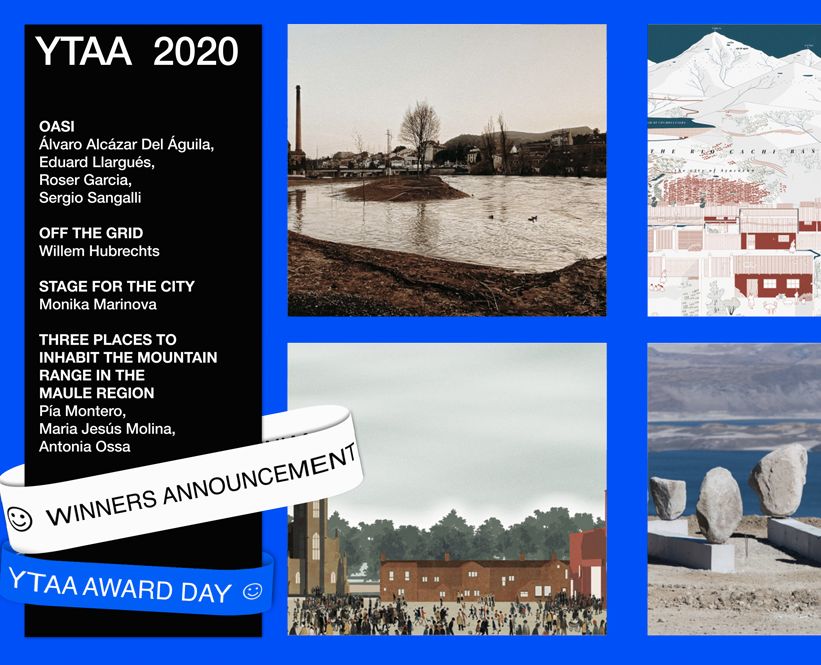

© Anna Mas